Life

Bettina Heinen-Ayech about herself

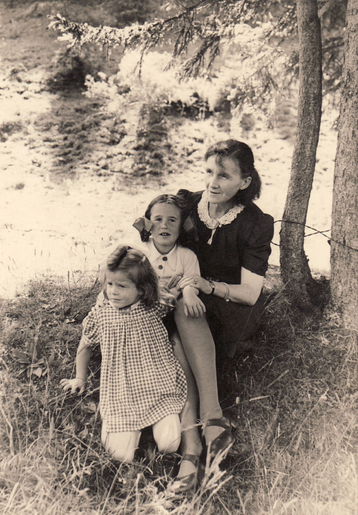

A childhood history

Despite the post-war years of famine and cold, my childhood and youth in Solingen was a happy one. I can still clearly remember how we all slept in the same room and lived off boiled turnips, as well as the first time we had bread and how my father got us to pray. My father would write poems at night, which my mother would always read to us and these without doubt made a great impression on my childhood.

Despite the post-war years of famine and cold, my childhood and youth in Solingen was a happy one. I can still clearly remember how we all slept in the same room and lived off boiled turnips, as well as the first time we had bread and how my father got us to pray. My father would write poems at night, which my mother would always read to us and these without doubt made a great impression on my childhood. My teacher, artist Erwin Bowien, exchanged paintings for food so that we wouldn’t go hungry. He would paint every day, despite the difficult situation. Our house was a meeting place for all those who loved art, music and literature, and they adored my mother who hosted them. I remember frequent visits from artists and intellectuals in my parent’s weekly “salon”. The following are just some of those who came to visit: the politician and art patron Dr Kronenberg, pianist Elly Ney, painter Professor Georg Meistermann, sculptor Lies Ketterer, writer Dr Heinz Risse and many others. My sister and I would make the long walk to Höhscheid and from there we would then take the tram to the August-Dicke school. We were reluctant to leave the house until my father would look up from the hall window and call out “sleep well”. For superstition reasons, we would often go back if my father had forgotten to say this affectionate farewell.

My school days

I always excelled at painting in school. The art teacher, Johanna Büsser, constantly praised and encouraged me. Erwin Bowien watched my development with joy. He was certain that I would become a painter when he saw the figurative portraits I painted of my nephew. However, I was also passionate about writing plays, travel adventures and poems. I was so obsessed with these that I would write fervently on the tram. My third passion - at which you can all have a laugh - was dancing. My German teacher, Mrs Schildmann, took an interest in my writing. She interpreted my essays in such a unique way that they weren’t censurable. My teacher, Mrs Dorothea Rusch, bought my first childhood pictures when I was 13 years old. My friendship and admiration for Mrs Rusch still exists to this day. During the school holidays, I either visited Erwin Bowien in Weil am Rhein to paint in the border triangle, or went with him to Klappholttal on the island of Sylt, a community college where many intellectuals and artists of the time worked and gave lectures. I had a preference for painting figurative young men.

First painting trips to Sweden, Norway and Tessin

Before I’d even reached the age of 18, Karl Schmidt-Rottlof saw my paintings at the Hanna Bekker vom Rath gallery in Frankfurt (in the Frankfurt art collection) and was extremely taken with them. He wrote to me saying I should stay focussed and true to myself. We often travelled to Sweden and Norway where I was enraptured by the landscape and its people. The Norwegian poet, Dagfinn Zwilgmeyer, highly praised my landscape paintings of his homeland and bought them. Mrs Zwilgmeyer was the daughter of an oil tanker skipper and I’ll never forget the sight of the giant oil tanker sitting in a fairly small harbour. When people told me that the owners of the tanker fleet lived in the little red wooden cottage in front of us, which looked so tiny against the giant steel ship, I thought of our old cottage in Solingen, which I suddenly appreciated as a result. If shipping company millionaires were living in their old, wooden house, then artists could also live in their old hill-side, half-timbered houses. In northern Norway, on the island of Alsten at the foot of the Seven Sisters mountain range, we were warmly taken in by couple Arna and Peer Milde, the former Port Director of Sandnesjon. The island’s residents would visit every evening to see how our paintings were progressing. This is the perfect working environment for an artist. The numerous trips to Norway greatly influenced my early creative years. These paintings were to be displayed at an exhibition in Solingen, where my early and later works would be exhibited together for the first time. The colourful experience was the light. Throughout Europe, the colour is crafted by the light. In Norway, the midnight sun with its grandiose colourfulness is unique. Another significant experience for me was Tessin, an Italian canton of Switzerland, which offered a contrast to the northern landscape with its subtropical plant life but still shared the grandiosity of the north. What I still didn’t know at that time was that the colourful splendour of the Tessin flowers would lead to Africa.

My time at art college with Professor Otto Gerster in Cologne

Now I mustn't forget my time in college. In 1954, at just 16, I went to art college in Cologne. At the time, it was called the Kölner Werkschulen. Bowien found it extremely important that I learn nude and portrait drawing and painting. He found being able to represent people the most important in painting. Leonardo da Vinci once wrote that art is all about representing one's fellow human beings and their souls. I really wanted to go to Professor Otto Gerster's class on monumental mural painting and took the entrance exam. The works submitted prior to and created during the examination allowed me to skip three years of drawing classes and Gerster accepted me straight into his class on monumental murals. There I was the only girl in the class apart from a highly talented Cuban German who rarely bothered to show up. When the guys in class started riffing with a series of nasty jokes, I would be locked out on the balcony until Professor Gerster rescued me and forbade them from doing that to me. From that time, I particularly remember Mr Kuhnhenn from Remscheid, who later became a Buddhist monk in Burma. Only later did two other young women come to our class and the guys began to swarm around them. This deeply offended me, because I was too young in their eyes to be of interest. We'd spend all morning and often half the afternoon doing figure drawing. Otto Gerster taught us the most important criterion: the proportions and correctly showing the subject's stance. Laypeople often don't know how difficult it is to present a figure convincingly. The biggest danger is that they will tip over on the paper or otherwise look off-kilter. Even the Romans unduly emphasised the standing leg in their sculptures. Actually, a painter ought to spend an hour every day drawing nudes. In the afternoon, we made cardboard boxes for murals. I didn't dare to represent several people yet, but concentrated on just the one person first. After we finished the box, we started painting with casein paint, which is something like gouache. I was always bothered by the white film left by the casein paint, but it disappears as the wet plaster dries. The technique was very similar to watercolour, because there is little you can do to change it once applied. Professor Otto Gerster had certain ideas about what a good picture should look like and gave us guidelines to this effect, which I often perceived as a mesh. I will never forget what he said: "Bettina, you don't want to face conformism." No, I didn't want to and still don't. I wanted to create my own shapes and colours and my own rhythm of the picture. The carnivals in Cologne back then were unforgettable. I partied for many nights in a row.

Academic years at the Munich Art Academy under Professor Hermann Kasper

After four years at Otte Gerster, I attended the Hermann Kasper at the Munich Art Academy, where I took classes in monumental mural painting and created several wall paintings. It’s a shame that I was never really able to practice mural paintings later in life. Along with mural painting, I painted portraits daily in Munich. Since there was often no model, the painters often posed as models for each other. In Munich, I got to meet some Scandinavian students. All of them were passionate about dancing. Every night, we, along with my painter colleague Peter Halfar, would dance in good old Schwabing. The goings-on were so intense that one day, an older master visited me and asked me to please not take his “apprentices” dancing every night as they were falling asleep in his classes the following day.

To the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen with Professor Paul Soerensen

It was almost certainly my friendship with this group of Swedes and Fins that propelled me to transfer to the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in Copenhagen, where I was enrolled as the first post-war German student. There, I was enrolled into the painting class of Professor Paul Soerensen. Under Professor Paul Soerensen I mostly created oil paintings. He placed great value on life-sized portraits of living models. I’ll never forget him saying that anyone who can paint an empty hill with clouds is complete as a painter. It was only in Algeria that I really understood what he meant. If a painter manages to achieve this and portray this motif in a truly interesting way, they are a real painter. The long winter was an impressive experience in which the classes were open until midnight. I was even involved in the 500-year celebrations of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts which the Danish king and his family attended. Danish paintings were far more subdued than their central European counterparts at the time, which brought me great peace and did my paintings the world of good.

Treading my own path

Despite all this, I was happy to finish art school and finally begin my own path into the world of painting, always lovingly encouraged and indiscernibly guided by Erwin Bowien. His paintings were full of life and expressing his feelings was important to him, just as it was to me. He painted wonderful city images from which I learned a lot. Not only is it extremely difficult to portray the perspective of a city, but also the perspective of a landscape. In Algeria, I found that young painters rarely, if ever, paint landscapes because they have never learned to see the perspective in them. Learning to see is the most important thing of all. When Erwin Bowien came with me to Paris in 1960 to show me the museums and paint Paris, I got to know Algerian Abdelhamid Ayech, who would later become my husband.

My life in Algeria

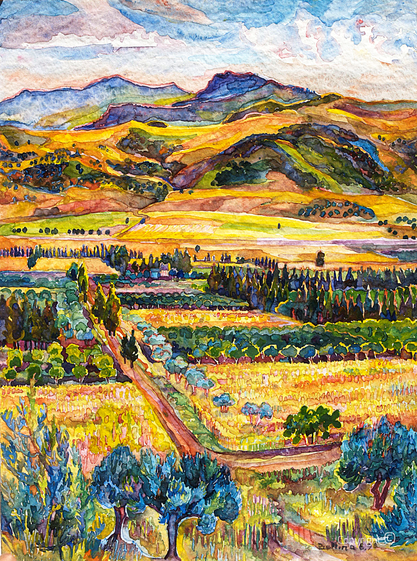

At the time, I had absolutely no idea about life in Algeria and was captivated by a mentality so different from that in Europe. I was instantly struck by his dignity and beauty, along with his kindness. In 1962, I was invited to exhibit by the Goethe Institut in Cairo. The exhibition was well received and the Egyptian Ministry of Cultural Affairs invited me to stay at an artist villa in Luxor where I got to know many painters and sculptors from Cairo. This interaction with a different world, imagination and religion was perhaps the most profound experience of my life. After returning home, I had just one wish, which was to get to know Algeria, Hamid’s homeland. In early February 1963, when the country had barely been independent from the old colonial French power for 6 months, we travelled by ship from Marseille to Annaba in eastern Algeria. I’ll never forget the rosé-coloured coast of north Africa that I saw from the ship. This sight made me feel as though I was arriving into a wonderland. During the first few weeks I began painting in Guelma, Hamid’s home town. My first Algerian landscape paintings were still characterised by Scandinavian impressions. The mountainous surroundings of Guelma with its fertile valleys were sometimes charming, but mostly powerful and impressive, just like in Norway. I tried to capture the exact colour that appears from the unbelievable light of northern Africa but which is bolder than any European colour. The soil around Guelma has a strong iron content and so is red in colour. Olive trees grow from this soil, which can appear cerulean or different shades of green depending on the wind and weather. They look like they are walking through the landscape. Sometimes I think of them as diamonds in the fields.

A fulfilled life

People were kind to me and, after seven individual exhibitions of which two were at the Algerian National Museum, I managed to make a name for myself there. However, I also exhibited each year in Europe and other Arabian countries, sometimes 3 to 4 times a year. I naturally got to know the Algerian artists who became like family to me. After all, artists are all looking for the same thing from this Earth, even if we take different paths. Abdelhamid Ayech, whom I called Hamid, supported my existence as an artist from a distance but with loving affection. Only now, after his death, do I realise how much he protected me from the stranger in me and was a calm influence in my life. I miss him deeply. This is just a brief overview of my life. My most important artistic companion was, and still is, Erwin Bowien. My deepest emotional motivation was my husband, Abdelhamid Ayech.

Bettina Heinen-Ayech, Guelma, June 1995

On 7 June 2020, the artist died at the age of 82 during a stay with her family in Munich. She had completed a flower painting shortly before her death and expressed her wish to soon travel back to Algeria. She is buried in the Munich Waldfriedhof cemetery.