Periods

Introduction to life and art by Bettina Heinen-Ayech by Hans Karl Pesch

A childhood history

Bettina Heinen-Ayech was born on 3 September 1937 in Solingen as the fourth child of journalist and poet Hanns Heinen. She grew up in an old, half-timbered house in the district of Höhscheid, on the edge of the city. A family friend, painter Erwin Johannes Bowien (1899-1972), recognised the child’s flair early on and decided to nurture this talent.

Little Bettina would often shake her red mane at the teacher, angrily stamp her foot and the dignified, old childhood home with its shimmering Persian carpet, mahogany furniture and slightly crooked oak beams resounded with her defiance. However, Bowien was an astute and knowledgeable teacher who kept his student’s temperament on a long leash and, instead of fuelling the fiery nature of the young talent, was able to contain it. Above all, the teacher encouraged the young girl to a great extent and taught her to capture bold colours in a symbolic way. He was probably the first to recognise Bettina’s unconditional talent.

Signet with which Bettina Heinen-Ayech has been signing her works since 1951

The impetus of Bettina Heinen-Ayech

Unconditional! This word is the key to Bettina’s imagery to this day. She never employed sophisticated restrictions to follow convention or boxed herself in. It didn’t bother her that her pictures often had nothing to do with one another. She worked passionately and spontaneously, painting things that she might otherwise not have; she never buckled under the challenge of what she saw and is a rarely found gem of what was portrayed. This ultimately explains the courage with which she approached the Algerian sky, land and people, even though she had developed the often contested artistic conscience of her teacher long before as a student, and would now be captivated by - and sometimes even agonised over - a certain motif that had suddenly appeared. This brings us to the reason explaining the constant authenticity of Bettina’s art, through to a clearly Algerian national painting!

Teacher and student

Let’s go back to the teacher and student. Erwin Bowien never objected to what the little girl painted as though he were reenacting a biblical story of creation. The 17-year-old portrayed mountains with ease. With yellow talons, rays of sunshine clutch the hurricane-like sky and traumatic valleys. This was all vividly expressed in watercolour across two square metres. At collective exhibitions, one suddenly understands what Bettina is portraying. One must stay standing, not shy away from it and feel the enormity of its hold, how eternally 20 years in Algeria characterise the culture and humanity of this art: a victorious fruit of isolation! Her paintings are also a journey to Algeria, to Bettina’s family and to the people of this northern African country. An expedition in her little long-suffering Renault across thousands of kilometres of desert to the ruins of Roman towns and the oases with their clay building settlements.

A turbulent talent

Let us revisit the young girl once more, who delivered watercolour suns and who received encouragement from no other than Karl Schmidt-Rottluff: “Bettina, stay true to yourself!”. At that time, Frankfurt gallerist Hanna Becker vom Rath became aware of the turbulent talent and, despite her being only 18 years old, included her paintings in a representative exhibition of German modern art that would be seen worldwide. Bettina Heinen from Solingen suddenly found herself on the same standing as Paul Klee, Max Beckmann, Max Ernst, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Käthe Kollwitzl and there were no critics who might have impeded her: “...we would have liked to have seen more from her”, reported a Brazilian newspaper.

About her academic years

Meanwhile, Bettina’s enthusiasm was at that time being nurtured. She was a student at the Cologne Art and Craft School and slaved away in the class of Professor Otto Gerster with anatomical drawings and monumental wall paintings after Erwin Bowien had recommended the large format and recognised her unique talent of mastering this. Prior to this, the student had attended the August-Dicke school for girls in her local town of Solingen and gratefully remembers her art teacher, Johanna Büßer. It was not easy for Bettina to gain recognition for the emotionality of her art at the Cologne art school. Nevertheless, she was put forward for two North Rhine Westphalian state scholarships (1959 and 1962). Next training phases: Munich Art Academy, Professor Hermann Kaspar, monumental wall painting and portraits and the Royal Danish Academy of Art in Copenhagen, Professor Paul Sörensen, free painting and figure drawing. With her perspectives and unorthodox use of watercolours, academically Bettina was considered a difficult student; some of them could be viewed as an objection to the strict rules of the Academy rather than an acceptance of the teachings. Nevertheless, Bettina looks back fondly on her academic years, particularly at her time in Copenhagen. She will never forget the unique darkness and light caused by the rain and snow, along with her experience of freedom. For the first German student to attend the academy after the war, the academy building remained open until midnight. Although the oil paintings she created at the time are barely recognisable as hers today, the challenge of asserting herself was important for us. In doing so, she learned to better understand her nature from the world of Nordic painters such as Eduard Munch, Solberg, Kittelsen and Carl Larsson. This visibly formed an awareness of her own will. This was strengthened by Norway’s intense landscape and with long summer weeks spend on the island of Alsten and Lake Mjössasee. Bettina became in the north what she is today in Algeria: a true testament to unmistakable landscapes. So, let’s gather ourselves as the early days are chronicled in an early monography about Bettina by Dr Eduard M. Fallet-von Castelberg. It also involves painting trips to Tessin, Greece, Egypt and the long applied variety of exhibitions (1967, Kleiner, Bern publishers).

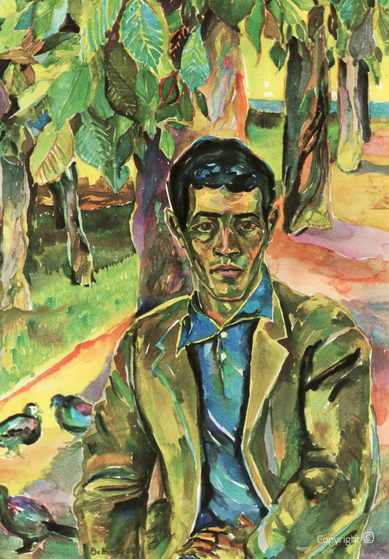

Erwin Bowien - a companion throughout her career

Alongside Bettina’s development through to Algeria, we must continue to talk of Erwin Bowien, her companion throughout her career and travels outlined here. He is as significant as any other teacher in the painter’s work. But let us hear about him from Bettina herself: “I only began consciously learning after his death. During my youth, I would often rebel against him. I didn’t want distance, rather, I preferred proximity. His discretion, his tact and the intimacy of his feelings contradicted my fiery temperament. Initially, I mistook the stylistic capturing of the essentials as intimacy. I always wanted to exaggerate in the dramatic sense. My aggressive, inquisitive nature allowed me to escape my own paintings to those of Erwin Bowien. His sophisticated nature, his colours and his painting seemed a constant reminder to me of the barbaric nature of my art.”

About her character

Bettina’s self-discovery towards her teacher, however, invoked a characterisation of the student by Erwin Bowien. In 1965, he wrote: “The first real surprise when developing Bettina’s talent was her vivacious, joyful capturing of natural phenomena and her bitter struggle with it: portraying the moving sea around Sylt, the Matterhorn mountain and Tessin were her first dealings with the world. Very soon, she took a path that led to a more streamlined approach. She overcame her naive joy of cheerful portrayals to become dominated by a constructive spirit. A clear separation of local colour and light colour could be seen. Her unique style is powerful and intentional, her purpose unflinching and deliberate. She is not prepared to materially see the human being and its soul. There is no crafty reckoning or intellectual plagiarism in her work. Everything that she sees is echoed in her own being. In the way that a composer portrays the human soul in musical form, she finds colour and style to elevate the painted subject to a spiritual level. The people portrayed by her are never fully released from God’s earth...”.

Impressions from Bettina Heinen-Ayech's hometown Solingen

About the childhood home

The study and painting trips around the world always led back to the Heinen home in Solingen, to her father, Hanns Heinen. For almost ten years, he was editor-in-chief of the “Solinger Tageblatt” and steeled himself with scepticism and a visibly insurmountable outer calm, a necessary requirement for spiritual self-assertion during the war and post-war years, to achieve the sensitivity of a poet who shone with his poems published in Bettina’s book. Her mother, Erna Heinen-Steinhoff, was a woman who would be remembered as mysteriously illuminated, an intelligent guardian and wise inspirer. In this house, all thoughts and artistic expressions were more important than material items. The silent, external reclusiveness was festively broken when the rolls of photos were unbundled upon her return home. The painting was always an accompaniment to the words, as being in the home of poet Hanns Heinen meant experiencing art along with an obligation of expression. Looking back at those years now, Bettina says: “What I experienced during my youth from my parent’s home and my teacher formed the backbone for my life in Algeria which often involved solitude.” She broke away from her youth in 1960. Acquaintance with Abdelhamid Ayech in Paris! The silvery grey city compelled new colours. The Louvre! Fear! Images of chimera!

Impressions from Guelma at Bettina Heinen-Ayech's arrival in the 1960s

Departure to North Africa

On 3 February 1961, daughter Diana was born. However, it wasn’t because of Abdelhamid that Bettina first went to North Africa. In 1962, she was invited by the German Institute of Culture to exhibit in Cairo and used the opportunity to travel around Egypt. Looking back, it was clearly a sign of fate, as her world was forced open as Bowien expressed. Bettina’s African experience was so different from the world she knew that Bowien spoke of “new eyes and new values” and wrote down that a young artist “wanted to be personally involved in the burdens and essence of the people there”. He had found what touched people about Bettina’s art in Algeria! Her artistic direction focussed on pure daily-related themes. It was precisely that which let the European effortlessly overcome some of the difficulties of life in Algeria, even turning them into positives for her work.

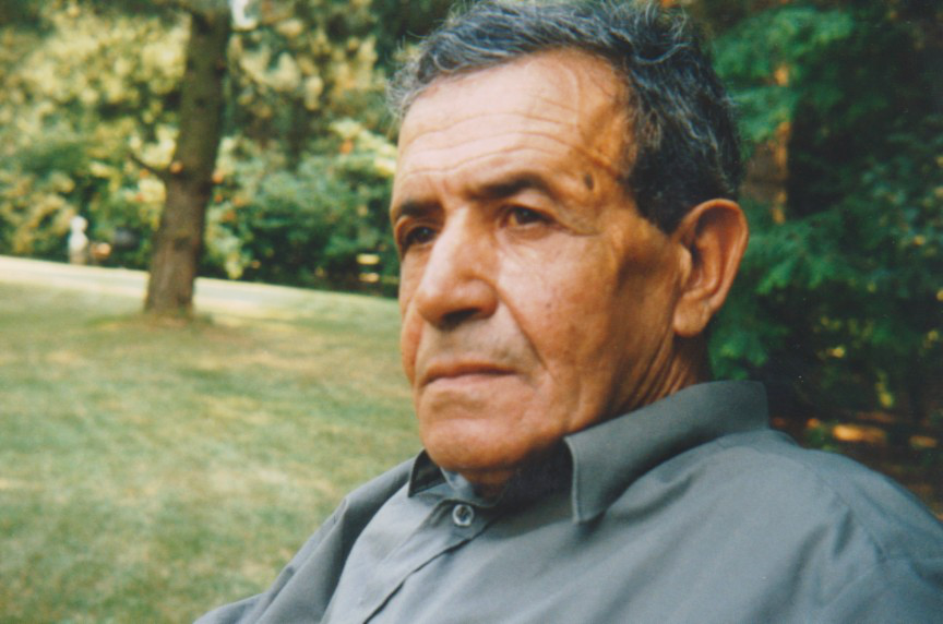

Portrait photos of the quarry owner and building contractor Abdelhamid Ayech (1926-2010), the husband of Bettina Heinen-Ayech

A life in Algeria

Her departure to Algeria with Abdelhamid took place a year later, on 03/02/1963. Their initial plan was to spend three weeks visiting family. The family has now lived in Hamid’s town of birth for almost five decades. The first picture painted by Bettina in Algeria was of a backyard with views of the former small dwelling in the centre of the town: washing is seen flapping in front of a dark wall. The leafless knot of a wine stem and an old shop window are transformed into a paradise of orange and gold and glassy green. A heavy dark blue curtain blows, from the scarlet red blossom that bursts out like stars... Like this first picture, many others that followed were inspired by Oriental decoration. And so, Bettina quickly developed the ability to transcend the purely external and reach the “source” as she calls it.

Since moving to Algeria in 1963, Bettina Heinen-Ayech has, in addition to her usual signet, occasionally also used this signet, which represents the Arabic spelling of the name Bettina.

Landscapes around Guelma 2000 - 2020

The main era in Bettina’s artistic life

Over the course of the years, this grew from portraits to visionary. No sightseeing with Bettina. Historical wisdom would be awaited in vain. The cultural motif rarely had more significance to her than incidental vedute. The conflict does not appear on the picture surface; rather, it takes place behind the picture. The range between presence and coming can be seen in particular from the portraits. They steer clear of garrulous communication. But isn’t it precisely this nature of painting that seems so threatened by the editorial-like wordplay in this country today? The voicelessness of the pictures communicates far beyond words! It is precisely this power that is found in Bettina’s art through the grandness of a sunlit landscape ignited by genuine encounters with people. Since all of this somehow evades precise explanation, while at the same time an accomplishment at the core of Bettina’s work, it is for her to give the word: “In the beginning, I painted the country with an insatiable enthusiasm for the bold formations and adventurous change of the seasons with wild romanticism. Soon, however, I quickly realised the perfect presence from which this landscape exists”. Bettina describes the term “perfect presence” as follows: “A typical outlook in Europe always awakened the impression of transition. Somewhere behind it lies the sea. This longing, the painter believes, inevitably roams further in Europe. In Algeria, an outlook gives me the impression of finality; and it is up to me to capture the reality of this in its countless forms through my work.” This can be seen in the fifty faces of the Mahouna mountain; and one won’t find any repetitions. As in a cyclical sequence, an increasing occupation can be seen as a foray into the source. This term is brought up again, as Bettina herself interprets: “I do not want to limit nature to a motif but rather capture it in its entirety. At the same time, it becomes an even greater part of my being.” Certainly, such conflict cannot be separated from the reality of the pure painting process, particularly when painting in the hot south. Bettina creates her landscapes in front of and amidst nature. She often has to undertake long trips alone and limit herself to the absolute necessary. Her technique is crucially defined by the fact that the colours dry immediately on the paper. This prevents the typical process of watercolour painting. The colours are placed together in an almost mosaic-like fashion, which is the reason for the extraordinary brilliance of Bettina’s paintings. At the same time however, this prismatic decomposition is compelled to become a compositionally calculated image architecture. As a result, the key external elements are identified.

Bettina and the colours

Ever since her youth, Bettina opted for bold colours, whether the subtropical vegetation of Tessin or the light of the midnight sun in northern Norway. In Algeria, however, she discovered bold local colours as well as glowing light: the red of the metalliferous soil, the intense green of young wheat, the gold of ripe corn and the magnificent colours of yellow and orange blossom. The colour is always portrayed in its true form to do justice to the symbolic exaggeration. The midst of Bettina’s work seems to have been achieved in 1965. It was met with success far and wide. While perceptions of the Norwegian mountains once warranted showcasing panoramas, the formations now flowed into the unremitting. The charcoal drawing became powerful. Rhythm was found in the pictures. The painter created hillsides of olive trees, fields of sunflowers, poppy fields, meadows and palmeries (sometimes in wall-sized format), whereby she diligently worked to bring out the detail as a whole and preserve the scent and clarity of certain still life flowers with great daring. The once so eruptive talent increasingly gained the ability to find a calmness in her abilities. Bettina recognises that herself: “After years of travelling, searching and exerting my craft, I’ve now found my place.” An intimacy reminiscent of Bowien’s or an arabesque charm can increasingly be seen. The painter has also become an “artiste” as the French say.

Personal development

To summarise her development in a phrase: In 1965, Bettina ventured into the typical. Since then however, her art advanced to become more refined with a personal quality. The same applied to landscape paintings as well as portraits. With landscapes, the personal refinement points back to the withdrawal of Bettina’s earlier peculiar style. An even more consciously colourful portrayal was employed, yes, one can understand why Bettina spoke “of infiltrating the spirit of a landscape” and can feel what it means when Bettina says she increasingly experiences the landscape as part of her own self. So let us hear from the painter herself again: “I don’t have a concept of time in the European sense during my life in Algeria. I have time to paint, time to think, time to read - in short: time to live. Of course, there is also a feeling of solitude. But I start to capture the essence of the moment.” Bettina fears that this may barely be understood in Germany since the present is instinctively viewed as the past. “However, the natural dignity of the simple people here helps me to tap into the essence of the moment. I feel less and less affected by the problems I read about in letters: I must feel so alone here, my enthusiasm will wane - and: how can I live without European culture? I feel that such letters are becoming more mechanical, meaning that the thoughts and feelings are blunted from a lack of time and reflection and no longer have any significant content. In these moments I’m particularly aware of how much I love Algeria and feel accepted by the people here”. This is how Bettina also explains her admirable relationship with intellectuals. They barely feel the unavoidable reservations, barriers and rivalries of Europe with artists.

Epilogue

What often seems abrupt and rash, with the innocuous flood of pictures from a friendship circle across many countries every now and then and 85 individual exhibitions, each year the contradiction is less and less prevalent. The paintings of the gaps of the Atlas mountains, the views of towns pouring out of the sand, the swaying palms, the dust in the oasis towns, the solidification of remote Bedouin forts, the stony index finger to the caravan routes, lonely tombs, views of the sea: none of these are simply images or even placards; the people depicted are not sitting for a portrait but instead, the paintings reveal a truth that calls the picture into question. The painting of new motifs does not lead to harmony; instead, like a fugue, to different resemblances! Sublimation from the growth of life and vibration, sublimation as consolidation and not as virtuosity. Culture is always painful for Bettina. This is highlighted in her paintings.

Hans Karl Pesch

On 7 June 2020, the artist died at the age of 82 during a stay with her family in Munich. She had completed a flower painting shortly before her death and expressed her wish to soon travel back to Algeria. She is buried in the Munich Waldfriedhof cemetery.